The Layout of Modern Manga

From the pioneers Osamu Tezuka, Sanpei Shirato and Shigeru Mizuki, followed by Yoshiharu Tsuge, Daijiro Morohoshi, Katsuhiro Otomo and others.

Translation by: Harley Acres

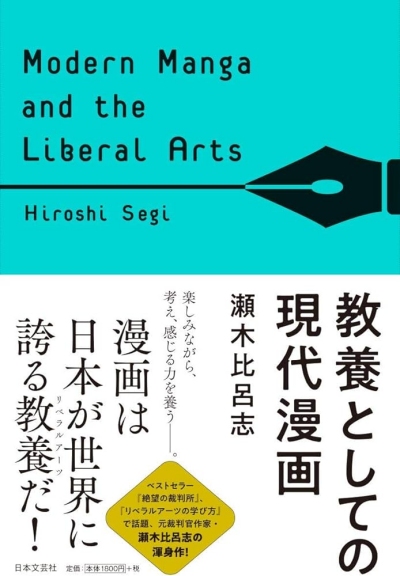

On January 29, 2019, Modern Manga as Education (教養としての現代漫画/Kyoyo to Shite no Gendai Manga) (Nippon Bungeisha) will be published. Even though manga has been published and read in vast quantities, there are not many books or guidebooks written that clearly define its place as a culture or provide a general overview of manga.

On January 29, 2019, Modern Manga as Education (教養としての現代漫画/Kyoyo to Shite no Gendai Manga) (Nippon Bungeisha) will be published. Even though manga has been published and read in vast quantities, there are not many books or guidebooks written that clearly define its place as a culture or provide a general overview of manga.

This is a full-fledged guidebook for people who are interested in manga but don't know what to read, people who want to read works by manga artists other than those they have read during their publication, and people who want to have a comprehensive view of manga.

Therefore, this book is the first of the "specific theories" addressed in How to Learn the Liberal Arts (リベラルアーツの学び方/Riberaru Aatsu no Manabikata) (Discover Twenty-One), and depicts the outline and history of contemporary Japanese manga.

From the viewpoint of empiricism and pragmatism in the broadest sense, I believe that it is a broad cross-section that encompasses everything from the natural sciences to the social sciences and humanities, philosophy, criticism, non-fiction, and even various arts.

Although the term "art" still has a lack of familiarity in Japan, it has not been used in everyday language, but I consider it to include not only art in the narrow sense, but also various types of popular art. Rather than categorical distinctions, the question is the quality of each and its universality.

That's why for the 43 manga artists I featured in this book, I focused on the quality of their work, and my primary criteria was whether they were able to express themselves in a way that only manga could, and whether they were comparable to other forms of art or other forms of expression. The selection was made on the basis of the work, with the second criterion being whether it achieved a certain level of universality.

The above is the gist of the sections up to Part 1, "While enjoying modern manga, feel and think about modern Japan and the world."

In the second part, "Three Pioneers of Modern Manga," we will select Osamu Tezuka, Sanpei Shirato, and Shigeru Mizuki as the pioneers of modern manga from the mid-1960s onwards, and discuss their works. It discusses how this trio were pioneers and influenced subsequent manga. [1]

In the second and subsequent parts, we will first discuss the artist's essence, and then, in the work introduction section, we will briefly explain and evaluate their representative works, including numerical evaluations from 10 to 1. The rough idea of this numerical rating is that 3 to 5 is worth reading, 6 and 7 are excellent, 8 is a semi-masterpiece, and 9 and 10 are masterpieces. In other words, "the number ranking which might traditionally be around 7 to 10 has been expanded to 3 to 10."

This is because, if this were not the case, all the works listed in the work guide would be ranked between 7 and 10, and the subtle differences would not be visible.

Parts 2 and 3 include cover illustrations and images from the work, and Part 4 includes only illustrations (although for one person I was unable to obtain permission to publish their imagery in Part 4).

Yoko Kondo, Rumiko Takahashi, and Fumiko Takano, all born in 1957

In Part 3, entitled "Nine Leading Contemporary Manga Artists," we have selected the following people. Yoshiharu Tsuge is sometimes referred to as a manga artist of the personal narrative style, but his world is far from being contained within the framework of the so-called personal narrative, nor does it show the absolutization of one's own senses and impressions that is characteristic of the personal narrative. [2] The greatest achievement of Tsuge is that he has greatly expanded the framework of contemporary manga through his excellent works of various tendencies, and in doing so, he has depicted his theme of escape from the world and his desire for seclusion from all sides. In the artist theory section, I discuss Life at Cape Komatsu (コマツ岬の生活/Komatsu Misaki no Seikatsu), Dog at the Mountain Pass (峠の犬/Touge no Inu), The Willow Shop Owner (やなぎ屋主人/Yaginagiya Shujin), and others.

Daijiro Morohoshi is a manga artist who has always dreamed of "a world before it was named," a world of innocence, where good and evil are undifferentiated, but when looking at his works as a whole, I find that, like Tsuge's work Morohoshi depicts, "a world that is highly organized and extremely sophisticated, yet a hugely uneven society." It can be said to be both a caricature and a study of Japanese society. [3] In his author theory section, I cover The Living City (生物都市/Seibutsu Toshi), Once Upon a Dead Man, (むかし死んだ男/Mukashi Shinda Otoko), Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard (ぼくとフリオと校庭で/Boku to Furio to Koutei de), and Under the Tree of Dreams (夢の木の下で/Yume no Ki no Shita de).

Katsuhiro Otomo was a typical manga genius. To understand his world, it is necessary to read not only his masterpieces Akira and Domu (童夢), but also many of his short and medium works in chronological order. At the height of his creativity, he showed minute changes in his drawings every few months. Otomo's dry, hyperrealistic and immediate view of the Japanese people and Japanese society has had a decisive influence on those who followed him. [4]

Mikio Igarashi, in contrast to Otomo, is a late bloomer. His career clearly peaked with I (アイ), a story of a private search for God in a secular world, but before that, To the Village of Kamuroba (かむろば村へ/Kamuroba Muri he), a full exploration of the current "secular" world of a Tohoku village, and Today's Words (きょうのおことば/Kyo no Okotoba), a cute and sophisticated gag piece, are both equally outstanding. [5]

The year 1957 produced three outstanding female mangaka from Niigata Prefecture: Yoko Kondo, Rumiko Takahashi, and Fumiko Takano. [6] The fact that all of these women started their careers around 1980 was due in large part to the fact that Japan had reached a certain level of sophistication as a developed country after a lull in its rapid economic growth, and women were considerably freer than before, and had the psychological freedom to pursue their own artistic methods. This is thought to be largely due to the social background of the time.

It is also noteworthy that their generation is the first generation of female manga artists to be freed from the shackles of shojo manga.

Although Takano reinterpreted the tradition of shojo manga up to a certain point in her career, she did not draw "shojo manga within that standard framework," and Kondo and Takahashi had no influence whatsoever from shojo manga in the first place. The postwar style of shojo manga was deeply affected by a Western (French and American) complex, but it can be said that the generation born in the late 1950s had finally begun to take on a new perspective. [7]

In the author theory section, I will talk about Kondo's work such as Mizu Onna (水の女), Yugao (夕顔), and Ouma-ga-hashi (逢魔が橋), and with Takahashi, I will talk about Kyokai no RINNE (境界のRINNE), Mermaid's Scar (人魚の傷/Ningo no Kizu), Middle-Aged Teen (おやじローティーン/Oyaji Rotin), and others. For Takano's works I will discuss Dmitri Tomokins (ドミトリーともきんす), Tanabe no Tsuru (田辺のつる), Genkan (玄関) and Watashi no Shitteru Ano Ko no koto (私の知ってるあの子のこと).

Tsuge, born in 1937, Morohoshi, Otomo, Kondo, Takahashi, and Takano, all born between 1949 and 1957, and Igarashi, who was born in the same period and has broadened his world in recent years. It can be said that the approximate framework of expression and influence in contemporary manga was established by these people and their generation of manga artists.

Those who followed were those born in the 1960s and later. By the time they began drawing in the mid-1980s, Japan had already become a stable, sophisticated, advanced capitalist and consumer society, and as mentioned above, the framework for modern manga had been set by their predecessors. Therefore by the mid-1980s, its expression has become more individualized and has also intermixed to a greater degree with subcultures such as computer games. Some mangaka were already actively using this mix of media.

Some of the more notable names include Hitoshi Iwaaki, Akira Saso, Minetaro Mochizuki, Iou Kuroda, and Minoru Furuya, but for the remainder of Part 3, I have chosen to focus on Fumiyo Kono and Daisuke Igarashi for the quality of their work and for adding a new area of manga expression that had not existed before. [8]

Kono gained popularity and acclaim for Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms (夕凪の街 桜の国/Yunagi no Machi, Sakura no Kuni) and In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に/Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), which chronicle the lives of ordinary Japanese people from the war years to the postwar period. The fact that Kono, who not only did not directly experience the war but also comes from a generation born more than twenty years after the war, was able to create such a memoir nearly sixty years after the war must, of course, be related to her own qualities, which I makes clear in the section on my theory of authorship.

Igarashi, while taking a broad view of foreign cultures, is even more thorough than Morohoshi in his cosmopolitanism. He sees Japan and foreign countries from a single, connected perspective and clearly depicts the animism and faith that pervade these cultures. In addition, the poetic depth of his work is unprecedented. His overwhelming drawing ability and intuitive grasp of the world and the totality of things make his powers of observation and insight outstanding. He is the first manga artist in a long time , perhaps since Tsurugi, Otomo, Takahashi, and Takano who has the impression of being a genius. In the section on artists, I discuss Sunakake (すなかけ), Children of the Sea (海獣の子供/Kaiju no Kodomo), Hanashippanashi (はなしっぱなし), and other works.

The above three parts of the book take up the middle of the entire 340-odd pages.

Footnotes

- [1] Osamu Tezuka (手塚治虫) is the "God of Manga" and easily the most influential mangaka in history. His major works include Astro Boy (鉄腕アトム/Tetsuwan Atom), Black Jack (ブラック・ジャック) and Dororo (どろろ) among many, many others. Shigeru Mizuki's (水木しげる) is an iconic figure best known for his manga Gegege no Kitaro (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎) as well as his autobiographical manga focusing on his time as a soldier during World War II. Takahashi speaks of her love of Shigeru Mizuki's work in this interview. Mizuki is important not only for his manga, but for cataloging the folklore of Japan. Many, if not most, of the yokai that appear in his work are actual yokai passed down through oral tradition in many small towns and villages throughout Japan. Mizuki researched, noted, and illustrated these creatures and spent many years researching and cataloging these stories. Additionally Mizuki is an important figure (among others) in the development of the gekiga (劇画) movement in manga. Sanpei Shirato (白土三平) is best known for his series The Legend of Kamui (カムイ伝/Kamui Den) and for his contributions to the foundation of the gekiga (劇画) style of manga. He is known for his historical manga including Ninja Martial Arts Handbook (忍者武芸帳 影丸伝/Ninja Bugeicho) and Watari (ワタリ).

- [2] Yoshiharu Tsuge (つげ義春), alongside Ryoichi Ikegami (池上 遼一), was an assistant to Shigeru Mizuki (水木しげる) in the early days of his career. His best known work is his short story Screw Style (ねじ式/Nejishiki). His work often mixes the autobiographical with elements of the surreal. His work was published in the alternative manga magazine Garo. He retired from producing manga in 1987. He is the brother of noted mangaka Tadao Tsuge (つげ忠男).

- [3] To learn more about Daijiro Morohoshi (諸星大二郎), please see our article and video on his works.

- [4] Katsuhiro Otomo (大友克洋) is not only a mangaka but also a film director as well, as he directed the adaptation of his own work, Akira which has gone on to become one of the most iconic manga and anime of all time. As mentioned here, in the 1980s his style was one of the most immitated (Rumiko Takahashi was asked about this in an interview and if she ever thought about emulating his style as well).

- [5] Mikio Igarashi (いがらしみきお) has won both the Kodansha Manga Award and the Shogakukan Manga Award for his work. He is best known for his four panel manga Bonobono (ぼのぼの) and Ninpen Manmaru (忍ペンまん丸).

- [6] Yoko Kondo (近藤ようこ) was a classmate of Rumiko Takahashi's and the two founded their manga study group during high school. Kondo is a devotee of Yoshiharu Tsuge (つげ義春). Her works include Roommates (ルームメイツ) and At a Distance (遠くにありて/Toku ni Arite). Rumiko Takahashi (高橋留美子) is, of course, the focus of this site, a detailed biography of her can be read here. Fumiko Takano (高野文子) is an artist that is influenced by the work of Katsuhiro Otomo (大友克洋) and is cited as a member of the "New Wave" that developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The Otomo influence can be seen in her story Bound for Shinjuku Station West Exit Keio Department Store Mae via Honancho (方南町経由新宿駅西口京王百貨店前行/Honancho Keiyu Shinjuku Eki Nishiguchi Keio Hyakkaten Zenko). Her other work includes Friends (おともだち/Otomodachi) and Lucky Girl's New Job (ラッキー嬢ちゃんのあたらしい仕事/Rakkii Jo-chan no Atarashi Shigoto).

- [7] For French settings in shojo manga one need not look further than The Rose of Versailles (ベルサイユのばら) and Héroïque – The Glory of Napoleon (栄光のナポレオン – エロイカ/Eiko no Naporeon – Eroika) both by Riyoko Ikeda (池田理代子). American set shojo manga includes Banana Fish by Akimi Yoshida (吉田秋生), Fire! (ファイヤー!) by Hideko Mizuno (水野英子) and by the 1990s, Moto Hagio's (萩尾望都) A Cruel God Reigns (残酷な神が支配する/Zankokuna Kami ga Shihai Suru).

- [8] Hitoshi Iwaaki (岩明均) is best known for Parasyte (寄生獣/Kiseiju). Akira Saso (さそうあきら) is known for Ain't No Tomorrows (俺たちに明日はないッス/Oretachi ni Asu wa Naissu). He also published in the same Godzilla special issues of Big Comic Original alongside Rumiko Takahashi. Minetaro Mochizuki (望月ミネタロウ) is known for his swimming manga Flutter Kick Goldfish (バタアシ金魚/Bataashi Kingyo) and Dragon Head (ドラゴンヘッド). Iou Kuroda (黒田硫黄) created Sexy Voice and Robo (セクシーボイスアンドロボ) while Minoru Furuya's (古谷実) most famous work is The Ping Pong Club (行け!稲中卓球部/Ike! Inachu Takkyu-bu). Fumiyo Kono (こうの史代) is known for her work In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に/Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni). Daisuke Igarashi (五十嵐大介) is known for Children of the Sea (海獣の子供/Kaiju no Kodomo). Additionally, Igarashi has cited Rumiko Takahashi and Akira Toriyama as early influences as well as the aforementioned Fumiko Takano.

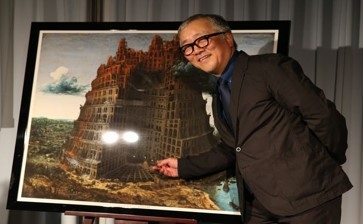

Hiroshi Segi (瀬木比呂志), Professor, Meiji University Law School, is a legal scholar, former judge and has written about legal issues and subcultures such as rock music and manga. He has written under the psudonym Makihiko Sekine (関根牧彦).